Today we continue letting the reader see some of the specific references behind the details in X-Day: Japan. These are not formal citations, as they are not all root sources and the book is not an academic volume. The use of real historical elements for X-Day: Japan serves to educate the reader about the time, add interest to the story, and honestly it just made the thing easier to write!

August 30, 1945

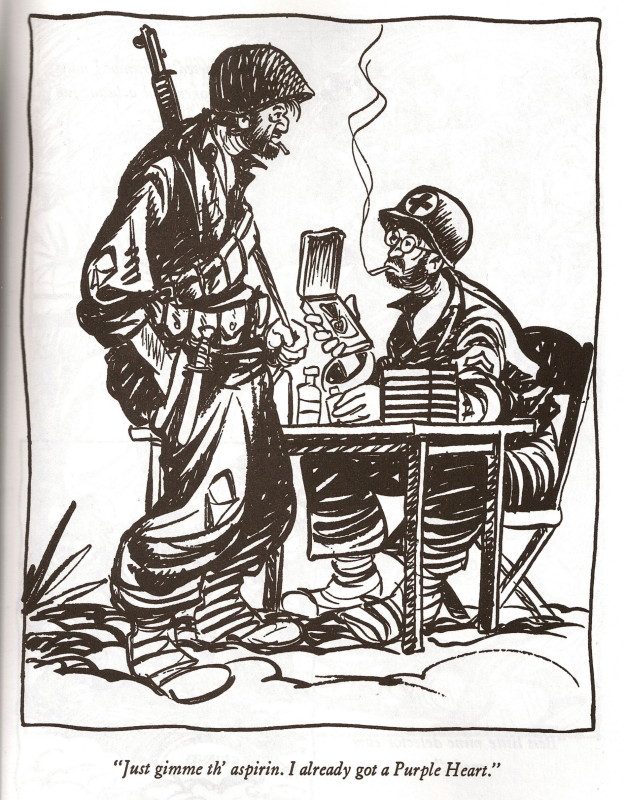

Purple heart orders and production,

– Giangreco, Hell to Pay, p187-193 [hardcover, 2009]

September 10, 1945

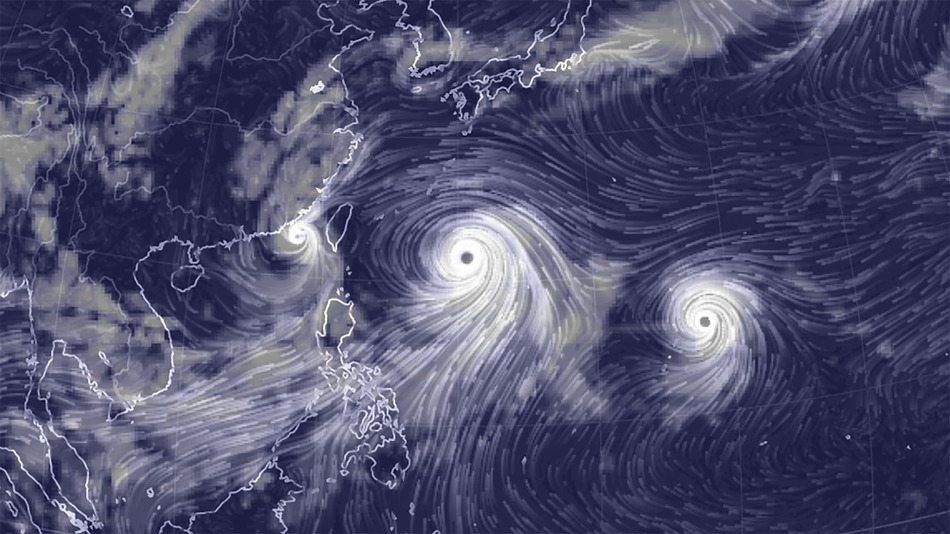

Typhoon Ursula,

– wikipedia.org

September 17, 1945

Typhoon Ida,

– wikipedia.org

– navsource.org

September 21, 1945

Antitank Rocket, Methods of Use,

– youtube.com

October 10, 1945

Typhoon Louise,

– history.navy.mil

– danielborgstrom.blogspot.com

– navsource.org

– glynn.k12.ga.us

October 11, 1945

USS Laffey, destroyer DD-724 [MUSEUM SHIP at Patriot’s Point],

– patriotspoint.org

October 28, 1945

Downfall operational plan, 5/28/45, Annex 3 – estimated lift requirements

– theblackvault.com

November 6, 1945

Petition to make Ernie Pyle’s house a national landmark,

– nps.gov

November 9, 1945

Men lined up waiting to use the head before an assault,

– Sledge, With the Old Breed

Surrender rates of Japanese soldiers,

– Frank, Downfall, p28-29 and p71-72 [Penguin paperback, 2001]

November 11, 1945

Diagrams of amphibious assault boats,

– ww2gyrene.org

November 16, 1945

USS Charette, destroyer DD-581, which had a remarkable career with the Greeks as the Velos,

– wikipedia.org

USS Montrose, attack transport APA-212,

– nasflmuseum.com

November 17, 1945

Helicopter medevac,

– olive-drab.com

– airspacemag.com

November 19, 1945

Estimate of Japanese tank strength and tactics,

– ibiblio.org/hyperwar

November 20, 1945

USS Sanctuary, hospital ship AH-17,

– wikipedia.org

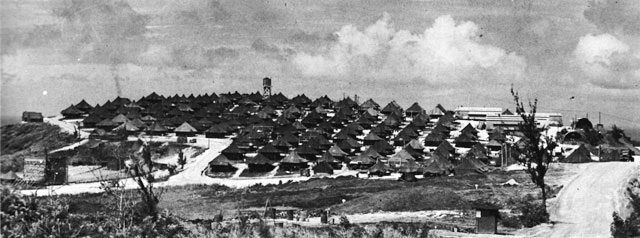

158th RCT, “Bushmasters”

– ww2f.com

– wikipedia.org

November 21, 1945

USS Athene, attack cargo ship AKA-22,

– navsource.org

USS Kidd, destroyer DD-661 [MUSEUM SHIP],

– usskidd.com

USS Chester, heavy cruiser CA-27,

– ibiblio.org/hyperwar

USS Windham Bay, escort carrier CVE-92,

– sites.google.com/site/windhambay

USS Comfort, hospital ship AH-6,

– dorriehoward.info/comfort

Blood supply,

– Giangreco, Hell to Pay, p139 [hardcover, 2009]

USS Firedrake, Mount Hood class,

– wikipedia.org

– ibiblio.org/hyperwar

USS Orleck, destroyer DD-886 [MUSEUM SHIP],

– orleck.org

USS Guam, Alaska-class,

– wikipedia.org

– wikipedia.org

November 22, 1945

USS Heerman (DD-532), USS John C. Butler (DE-339), – legends of Taffy-3,

– bosamar.com

– wikipedia.org

– navsource.org

“The outcome is doubtful, but we will do our duty.”

Rear Admiral Robert W. Copeland,

– wikipedia.org