[Tuttle got to watch Navy sailors in an amphibious landing practice, under live fire.]

The Heyliger ran parallel to the beach, from left to right, in front of where the assault boats were lining up at the hands of their green crews. We came about and made another pass in the opposite direction, as the three or four dozen boats finalized their formations (with much yelling and flag waving and not a few expletive-laden constructive criticisms).

Then the boats were off. We made a lazy turn out to sea to let them pass, then hurried in to move across behind them. At this point they were still about a mile from shore. Our five inch mounts roared out more shells, shooting over the heads of the men in the tiny bobbing craft, as many more and larger ships would do in a real assault.

Lieutenant Logan assures me that all the sailors have piloted these boats many times in practice. But this is their first live-fire test, and it shows. The natural instinct under fire is to duck – but it’s hard to drive a boat that way. Some boats drifted out of their lanes, then jerked back into formation. Some kept drifting, and I saw a couple near misses.

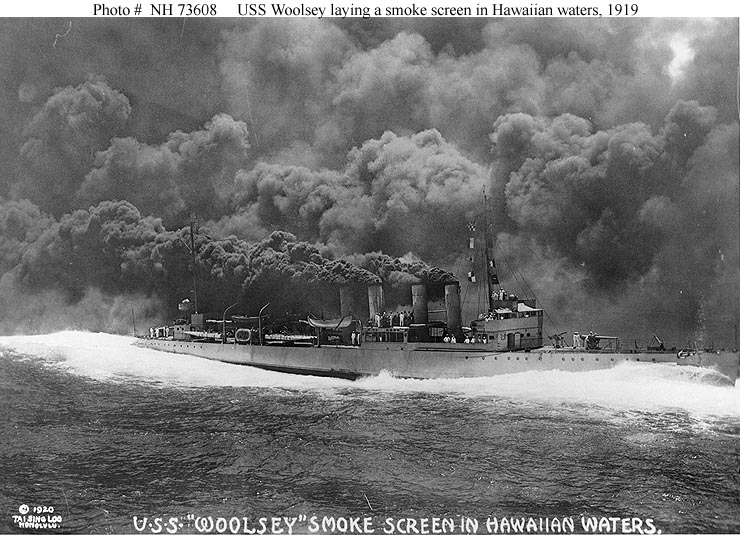

We got past the lines of assault craft, where I thought we would stop and watch. But we kept up speed and turned inland, quickly overtaking the first wave. Just when I was sure we would run aground the ship made another hard turn back out to sea, and we started making smoke.

The breeze was up and down today, but right then it was up. The smoke screen walked briskly down the shallows of the beach. Visibility couldn’t have been more than twenty feet. We couldn’t observe the boats any more, of course, but by this time observers on land were moving in to greet the boats, grading each young ‘captain’ on where he put his boat, compared to where it was supposed to be. It hardly seems fair, but unfairness is what some say is practically the definition of war.