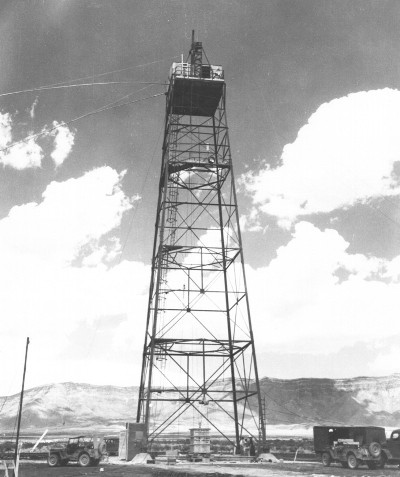

“What was that?

– blind girl, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, July16, 1945

The 75th anniversary of the Normandy D-day is upon us. While that D-day and the many D-days of the Pacific war are front of mind, X-Day: Japan is on sale! Look for eBook and paperback specials to add to your library or to present a summertime gift.

“Okinawa is about 5 miles across in its southern portion where we had four divisions abreast fighting stiff resistance for two months to advance about 15 miles, taking casualties all the way. Southern Kyushu is 90 miles wide, and we plan to land maybe 13 divisions. That would spread forces out almost six times as thin. Total area to be taken is well over 5,000 square miles. They talk about having ‘maneuver room’ and ‘flexible force concentration’ to overcome this. Time will tell. “

Easter Sunday, 1945, was also April 1st. In addition it was chosen as the start of the American invasion of Okinawa, cheerily code-named “Love Day”. (D-Day by this time had become a brand name, forever associated with the French Atlantic coast.)

In today’s post we want to point the reader to an excellent online book. The work focuses on Marines, but gives a good deal of both context and detail, from logistics challenges to combined arms problems.

nps.gov – The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa

The link starts at the second section of the book, where it is pointed out that the landing would put ashore six divisions, supported by an enormous fleet, while campaigns were still not finished in the Philippines or on Iwo Jima. This focus of power so far from the USA was a tremendous strain on the logistics chain in place, which at times would be a limiting factor in the American advance.

Such a heavy reliance on artillery support stressed the amphibious supply system. The Tenth Army’s demand for heavy ordnance grew to 3,000 tons of ammo per day; each round had to be delivered over the beach and distributed along the front. This factor reduced the availability of other supplies, including rations.

On land, facing clever and coordinated defensive infantry and artillery tactics, American forces were stymied to make fast progress (at acceptable casualty rates). With three divisions at a time, with replacement regiments rotating in, across a span of as little as four miles, advances were halting.

General Buckner favored a massive application of firepower on every obstacle before committing troops in the open. … Colonel Wilburt S. “Big Foot” Brown, a veteran artilleryman commanding the 11th Marines, and a legend in his own time, believed the Tenth Army relied too heavily on firepower. “We poured a tremendous amount of metal into those positions,” he said. “It seemed nothing could be living in that churning mass where the shells were falling and roaring, but when we next advanced the Japs would still be there and madder than ever.”

These oft-repeated quotes played an important part in gaming of Operation Olympic for X-Day:Japan. On Kyushu three times as many divisions would have to be supported over a front twenty times as long. Japanese reinforcements, from infantry to shovel-wielding workers, would continue to flow in. The monumental clash of forces would be ugly and slow. Medals would be awarded by the crate – if the crates could ever be delivered.

[Not included in the original Kyushu Diary, this Tuttle column is often reprinted on Chirstmas Eve. We share it this week marking the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.]

I made reference back on the 7th to the Pearl Harbor attack of 1941. For me this date, December 24th, Christmas eve, will always remind me more of that horrible fateful day. Because the destruction from the attack didn’t end on the 7th. One story of loss will stick with me. On December 8th tapping was heard from deep inside the partially sunk battleship West Virginia, where some number of men were trapped deep below deck. On December 24, 1941, the tapping stopped.

The West Virginia is here with us now, along with four of her sister ships from Pearl Harbor’s now infamous ‘Battleship Row.’ The trouble with sinking ships in a harbor, especially Pearl, is that you can’t. It’s too shallow. Big ships settle on the bottom, still half above the surface, and a good harbor has every facility one would want to patch up and re-float the ships. In fact the Nevada, the only big ship to get under way that morning, was deliberately grounded after she took damage so she could be recovered and repaired.

The hit at Pearl was a big one for sure, and permanent for thousands of young servicemen, but for most of the big ships ultimately only temporary. Certainly Japanese planners knew this going in. The U.S. Pacific Fleet was mighty thin for the next year, reduced to hit-and-run harassing strikes with the carriers that by luck weren’t there in Hawaii. But since then, with scores of new and repaired (and upgraded) big ships joining the fleet, it has leapfrogged the worst nightmares of those admirals in Tokyo.

Much has been said about fast aircraft carriers taking over from the battleships of old as kings of the sea. That may well be true on the ocean, where fleets have engaged in air duels well out of gun range many times across the Pacific. But here on dry land, I can certify that the battleship is very much respected, or feared, depending on which side you’re on.

Navy ships sail with bigger guns than any army even attempts to drag along on land. Any place on the Earth within twenty miles of forty foot deep water can be blasted by one ton shells from our newest big ships. Japan is an island nation, and all of her conquests outside of China have been more smaller and smaller islands. All of them are vulnerable to the wrath of naval ordnance over almost all of their surface. Planes could drop bombs of the same size, but low flying planes can be shot down with the smallest of anti-aircraft guns. The only defense against navy guns available to most Japanese garrisons has been to dig and dig and dig, deep down into the rock if they can, and wait to be flushed out by flame throwers once the Army or Marines land under the support of those big old battlewagons.

Here on Kyushu, we found the main beach defenses lined up just exactly beyond the range of most navy guns. At Ariake there were the reverse-slope positions our Navy couldn’t get at until sailing into the bay, and that cost us something. But outside of that, the best tactic the Japanese had was to leave old guns in dummy installations near the shore to soak up shell fire.

The ships that came back from the knock-down at Pearl Harbor were mostly older slower vessels, but they work just fine for work along the shore. Islands don’t move very fast after all. The battleships have been kept very busy. The USS New York just rejoined the fleet after having her guns re-lined. They were worn out from firing so many thousands of big shells at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Back to the story of the West Virginia. Re-floating a damaged ship does take some time. She didn’t make it into dry-dock for repairs until June 18, 1942. Before that many attempts were made by divers and search teams to enter the lower compartments and rescue survivors or recover bodies. That is also necessarily slow work. Cutting into a closed compartment will flood it, and possibly many more compartments if the hatches aren’t all closed. Letting a lot of air out and water in can destabilize the whole ship, sending it over and ruining all chances of rescue or recovery.

I have it on good authority, but off the record, that three young men were recovered from the last compartment opened on the West Virginia. By match light they had marked off the days on a calendar through December 23rd. The Navy has decided never to identify them. They will be officially listed as Killed-In-Action, December 7, 1941.

The days were finally starting to get a little longer. As the gray sky started to lighten we moved out past American front lines, climbing down a ways to cross a short flat. It was open rocky terrain and everyone felt self-conscious in our fashion ensembles of wet dark green.

The company advanced slowly in one double line up to the next hill, across the valley American troops had been watching for so many days. At the base three patrols split off, one to either side and the third moving up to the peak. The patrol I was with advanced cautiously around the right side of the hilltop. Just over the crest we found about a dozen shallow fighting holes. Abandoned shovels, packs, and a few rifles were left there in and around the holes. Also in the holes were three dead bodies.

It looked like the Japanese had moved up to that line the day before, or the previous night, and made a temporary fighting line. There was no fighting so the soldiers there had died of existing injuries. Outwardly they looked bloated, as if they’d been dead for days. A few odd large sores were visible on the head and hands of a couple of them. The private next to me tipped the helmet off one with the point of his bayonet, and clumps of thin dark hair came off with it.

Our senior sergeant growled out a quiet reminder about booby traps, and we left the bodies and materiel there for others to clean up. We advanced slowly through the rocks and leafless brush down the back slope of the hill. Over the next four hundred yards we found six more bodies, soldiers in ragged uniforms, some with whole limbs wrapped in dirty bandages. Most looked like they collapsed while crawling on all fours, away from our lines.

We had gotten ahead of the center patrol, and it was there from our left that one live solider came stumbling toward us. He moved out from behind the dark boulder he’d been leaning on in a staggering half-awake walk. His pathetic form did not carry a gun, and no one fired at him. His uniform was dirty like the others, but straight and neat, topped with a sharply creased brown cap. He had been their commander.

The young officer raised his sword with one wavering arm. One could see from twenty feet away that it was a cheap stamped steel model. The Japanese were mass-producing them for every new officer to make him feel like part of the ‘warrior elite.’ His jaw fell and the sores in this warrior’s cheeks opened to expose the tortured flesh inside his mouth. He attempted to yell but only made a raspy mewl. He was almost upon our left column.

The point man on that side froze, horrified and mesmerized by the almost inhuman apparition. At the last second he raised the butt of his rifle and deflected the sword’s feeble blow. The imitation samurai blade was slowly raised again, and a Thompson barked out a long burst. The second man in the patrol line put his slugs all clean through the officer’s wrecked body. That lifeless body fell at once into a disorganized heap of parts, barely recognizable as a human corpse.

[The first full day of the nuclear age dawned with American patrols missing and out of communication.]

Forest fires burned through the night, keeping a hazy glow above the northern horizon. Morning recon plane flights say that quarter to whole mile diameter areas were burned out. The bombs made clearings in the trees more thorough than area bombing and shelling could accomplish with thousands of rounds.

Light but steady winds had carried smoke and ash to the northeast. This put it all back over Japanese lines or empty rugged forest. Another reminder went out that fresh water sources from the high central forest, which was most of the supply for our lines, were not to be trusted.

By this morning radio traffic was largely back to normal. A few radios had simply quit working after the blasts, mostly ones that had been set up with units far forward. The battalion I was with was not the only one who had sent scouts forward against orders.

Our own scouting patrol finally made it back, escorted by a larger rescue patrol which had gone out after dark. Word is that they made contact with some Japanese. Both sides surprised the other in the dark and exchanged ineffective fire for almost an hour.

The original patrol had been up on a small ridge, looking out over the plain east of Takachihono-mine, when the first bombs went off. They got down behind the ridge but it was right in line with the last bomb and offered little protection from its flash. Their radio was completely shot.

They reported scattered Japanese activity all over after the bombs.

Positions up on the mountain all came alive ready for an expected rush. The American patrol hid for the day, planning to slip back at night. They would have come back fine without the rescue party.

I got all this second-hand. Both patrols were taken away into quarantine as soon as they got back by members of the 6th Infantry Division. That division did land yesterday, but not as a unit. They broke up into teams which went out to most American front line positions.

Teams of the 6th carried an array of bizarre looking equipment. They had portable radiation detectors, hand held units with shoulder bag batteries. Some machines rolled on two-wheel carts. Another looked like an industrial vacuum cleaner (which it was – it sucked up soil samples to pass through an enclosed analyzer).

Other odd contraptions could only be hauled on dedicated trucks, some of which looked hurriedly improvised. Men of the division tell me some civilian ‘eggheads’ came along. They stayed back near the beach, along with lead-lined gunless tanks which can roll out into the blast areas directly once we get there.

[Tuttle went looking for anyone who knew about the atomic bombing, or what would happen next. He had a long ways to go.]

Battalion command was set up in a tent a half mile back from the bluff top camp. Inside two men worked radios through every frequency in the current book, and got nothing but wild static. A few officers were talking over a map table, wrapped up in tense conversation.

A decision of some sort was made, and some of them left. I approached the table and engaged the senior man. Lieutenant Colonel Ken Olson commanded the battalion. “If you’re wondering, no, I don’t have the slightest idea what happened or what we’re supposed to do. And yes, I’m furious that they would blind side us like this.”

I looked over the marks on the largest map. “This is about where each bomb went off,” he explained, “each atomic bomb. We know that much, but only from what anybody can read in a science magazine.” A two mile diameter circle was drawn around each spot, which might be the effective kill zone of each bomb, but that was their marginally educated guess.

“Here’s my current problem.” Colonel Olson laid out a local map. “We have a patrol out there. They were supposed to observe this road, camp overnight and scoot right back.” He outlined the path out and back. “Someone thought they saw Japs moving out there. I approved the scouting operation, despite the pullback order. I can’t stand being both blind and chained down back here.”

He wasn’t sure what they were going to do about it, but the other officers had gone out to gather up the best equipment they thought might help and assemble a team to go find the missing men. I was about to leave when another courier came in. I’m not sure how difficult it is to drive a jeep in hood and mask and gloves, but that fellow had been doing it all day.

The colonel got four carbon-copies of a typewritten instruction sheet to pass out to his companies. It provided little new information and reinforced previous instructions: We should have seen six atom bombs go off, near listed landmarks (if one didn’t go off as planned we were to steer well clear). Blowing smoke might be dangerous if it came our way. Fresh water supplies should be topped off immediately and not refilled from anything downstream of the blast areas. Any Japanese soldiers which might either attack or surrender should be treated like lepers and not directly contacted.

[Witnesses to history, Tuttle and the soldiers around him didn’t know what the first use of nuclear weapons would mean, for them or anyone else.]

I stole a glance around and saw that everyone, to a man, was watching the unusual bomb run with me.

They say it was 9:12 am local time when the first bomber released its load and triggered the others to follow suit immediately after. Some men say they saw all five bombs in the air. I for one caught only a glimpse of the first giant steel ball just after it was released. I watched that pair of B-29s turn and dive steeply, right toward my vantage point. The other pairs pulled the same maneuver, leaving in whichever different direction would keep them best clear of the coming blasts. The first pair passed back overhead still diving, engines ripping madly at the air to pull the bombers away from danger. The high flying sentries continued to orbit over the area, a little to the south.

I was eyeballing the two laggards, which had passed the first pair on their way out. A great flash lit them up, brighter than a clear noon sun. Instinctively, though against instructions, I turned north toward the source of the light. In close succession, above the hills and trees in between, another four flashes lit up across the horizon. Each was similar to how the blast from a big navy 16 inch shell lights up the night, but this was in broad daylight.

An ethereal dome formed and spread out around each blast site, visible only by its effects. Cloud layers alternately formed or vanished as the dome passed. Walls of dust and smoke pushed out along the ground around each blast, quickly visible over the near faces of the mountains north of us. A flattened ball of burning air raised up over each of the sites I could see, shedding and re-swallowing smoky clouds as it roiled up through the hole each bomb had made in the atmosphere.

I remembered the late pair of bombers and picked them up again roughly over Karakuni-dake. The laden one had released its bomb and they had turned together to the east. Due north of my location they caught the first blast wave. Both planes suddenly jumped forward and up, while banked into a right turn. With their full profile facing the shock, they were hopelessly damaged instantly. Closer observers say one plane lost most of the right wing before being sucked directly into its partner. Debris rained over the 11th Airborne Division’s former staging area.

The last bomb detonated high over Takachihono-mine, barely two miles from the former front lines of the 40th Infantry Division.

I wrote some time ago about an ‘earthquake’ from artillery bombardment. I thought it was modest hyperbole, but it was not remotely close. Today a real earthquake moved the ground under our feet starting a few minutes after the first bombs went off. A great crack from each explosion was heard, followed by continued crackling that took some time to soften into an echoing rumble. Some men thought they felt the wind shift for a moment.

Men began to talk over the sounds, some of them excitedly whooping, some asking what it meant. The company captain had already gathered his officers and they were pointing at the burning mountains and marking up their maps.

Each explosion had been capped by a flattened ball or rolling donut of smoke and fire which rose steadily over a perfect column of hot smoke and steam. The ball shape stayed together until almost out of sight high in the sky. By then a great haze had spread over the entire horizon. Fires raged around each blast zone. A slight wind carried the smoke to the northeast, away from us and mostly across all the Japanese lines.

[A day after being ordered to pull back, Tuttle and his unit found fighting and all supporting operations were at a complete halt.]

I had completely forgotten what silence sounds like. In the last two months the sounds of combat had been a steady constant. The intensity varied only between loud and ear-splitting. From any position one heard artillery shells either being fired or exploding on impact – or both. Engines of trucks and aircraft filled the air between every echo of every distant rifle crack.

This morning I heard a bird. All of the mechanical noises were temporarily muted. Sounds of combat were not heard anywhere on Kyushu in those few hours. Lastly I noticed that there weren’t even any distant aircraft engines.

Without fail since before X-day American fighter planes had been flying long figure eights high over a line well to the north. Even in bad weather at least a few planes did combat air patrol up there, to detect and impede any Japanese air attack. Their constant drone was the last steady lullaby for sleeping soldiers on the quietest nights before today.

A second bird answered the first. I listened to their conversation as my current camp woke up. The sounds of clanging canteen cups were eventually joined by the first mechanical sound of the day. A jeep, driven fast and hard, stopped at the edge of our camp. It gave instructions to the nearest man and sped off again.

“If something big happens, don’t look at it! Stay low, keep ready, and wait for instructions. Pass it on!” Some men wondered aloud what it meant. Some asked why it wasn’t simply radioed out. Those who had gas masks double checked them. Many moved their foxholes to spots with a better view of the Jap lines.

A little before nine am the fighter planes came back, in force. Three broad waves came in from the south, at three different altitudes. They continued many miles north, to at least their old regular patrol line, then turned east or west out to sea. The lowest group took some anti-aircraft fire, at least one plane going down deep in the Japanese held forest.

[Just as a new offensive was gaining traction, Tuttle and everyone else was shocked at being ordered to pull back.]

A shock wave greater than that from any explosive shell ripped through American lines just after noon. All forward units, everywhere on Kyushu, got orders to pull up and move back to the previous good fighting line, not less than one half mile back – immediately.

The move had to be completed by nightfall. Also, every man was to check the state of his gas mask. Officers were to plan inspections of masks by no later than 9 am the next morning.

Whatever sort of uncomfortable shell-wracked muddy crap holes those men were in, they had fought for them. They were offended at the idea of pulling back. They did so anyway, but complained loudly to the wind, which should have turned red at the profanity it heard.

Field kitchens served men where they could before packing up, but some simply dumped a whole hot meal. Junior staff officers scrambled to figure out where people were, or were going to be, or simply to find room for everyone when units suddenly wound up on top of each other.

Still, the men assumed there was some marginally rational reason for the order (despite all previous experience with Army orders). Suppositions started with some use of chemical shells by the Japanese elsewhere on Kyushu, to wild stories of plague infested rats being loosed by the OSS.

I fell in with a heavy weapons platoon, making instant friends by offering to haul two cans of machine gun rounds. Once back to roughly where they would wind up, everyone sat down waiting for final orders from the battalion. Their commander, Utahan Lieutenant Levi Pace, took stock of the gas mask situation. Of 47 men active in the unit, ten had a mask with them. Six of those had a good filter canister.

A gas mask was on the fingers of every soldier on the morning of the initial landing. No one knew what to expect of Japanese tactics when Americans first invaded their homeland. Two months later, after zero need for them, most gas masks had been ‘misplaced’ as men lightened their combat load. The changeable filter canisters could be hollowed out to make cooking vessels or many other handy things.

The lieutenant tasked three men with running, as fast as they could, back to division depots for more masks. They were too late. Rear units had been there first, leaving only what supply men kept in reserve for barter. As night fell the platoon counted a lucky thirteen working gas masks, and had IOUs to fill with several division quartermasters.