[Sakura-jima was barely half American held when Tuttle squeezed onto the island among the thousands of troops already there.]

There was nothing else to see from my viewing position on the main land, so I made my way onto the island. It was a record slow two mile trip.

The only road onto the island and into American base camps was beaten up and overburdened. A mob of fresh troops, new equipment, and odd personnel like myself were trying to move onto the island. As many injured, tired, or broken men and machines were trying to move the other way.

All along the shore road burned vehicles, or pieces of them, had been pushed onto the black beach or over ledges directly into the water. In two spots along my way engineers had no choice but to close the road for some time while cratered sections were cleaned up, and whatever temporary structure or fill was available was put in to make the road usable for a little while longer. Ambulances were cleared through but then everyone else had to wait.

A few men pushed through off road on foot, but overnight rain made that sticky in some places. In sandy places those men will have picked up abrasive grit that they will be chasing out of their boots for days.

Everything was compressed into a narrow band at the base of the mountain. Since there clearly wasn’t enough capacity over the one road for all the division services to support its two cavalry regiments – and the Marines, which had only small boats connecting them to Kagoshima city – the facilities had to set up on the island. An artillery battery worked across a narrow alley from a field kitchen. A medical aid station was uncomfortably close to a pile of fuel drums.

Eventually I got through to the one substantial town on the south shore. It was a cluster of poor looking buildings, two blocks deep from the shore, formerly prospering in whatever fishing and commerce happened through its few docks and piers. North of the town was a gentle rocky slope, almost a plain. In it was a quiet spot, relative to every other clear area, which were all being put to immediate use.

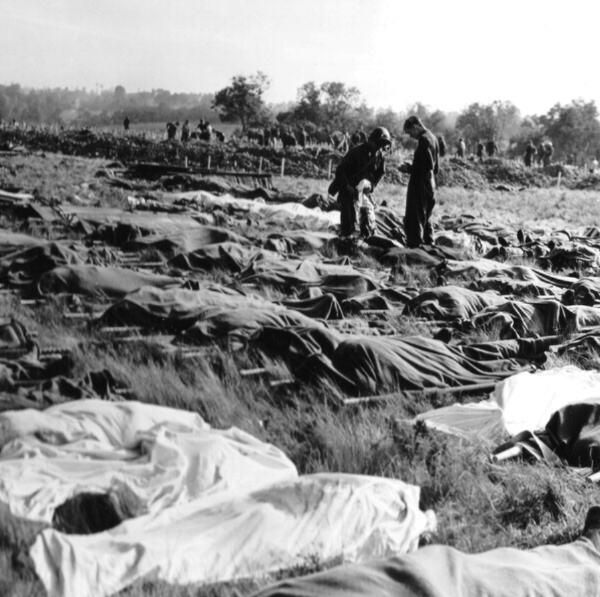

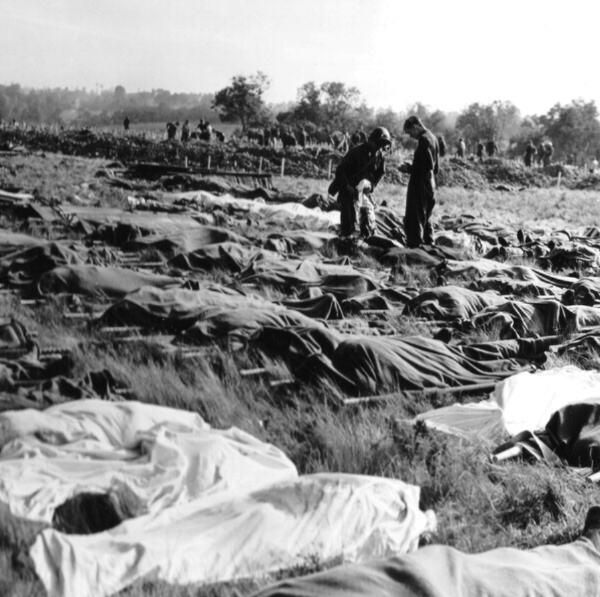

I walked up to find the quiet area was a temporary cemetery. Poncho covered bodies laid in neat rows. A crude signpost at the far end of each row I guessed must categorize the men there by branch and unit. A small team of men was unloading an assortment of vehicles at the far corner. The vehicles were lined up almost back into the town, each bringing over bodies that had come down the mountain or been discharged from a medical station.

I walked between the rows to where the team was working. Looking closer it was clear that some of the old ponchos on the ground covered only a portion of a human body. There were five men working the yard, rotating who was off as pairs of them carried each new case. They had a few stained stretchers to use. I offered my services to the chief NCO there, to make it an even six men working.

Staff Sergeant Bill Allen looked me over for a few seconds, unsure if I was serious I suppose. Few men volunteer for the job, even the drivers who bring over several corpses at once. I was paired with a young Army corporal and we got busy clearing their backlog. Footing was tricky in some spots, the day’s rain putting wet rocks or slick mud under foot, and making them hard to tell apart.

Corporal Warner Thompson hails from Fairfax, Virginia. Most of his infantry unit is doing back-line jobs like this one. Their part of the 5th Cavalry was hit hard and probably won’t do much until it can get off the island to rebuild. We talked about his experiences in the fight, and about life back home, and pretty much everything except what we were doing.

Finally he broached the subject, by way of a standard soldier’s gripe about getting a lousy job. I asked how long he’d been at it. “This is the third day. They had us stack ‘em here almost right from the start.” Getting ambulances back and ammo forward took priority on the narrow road.

I asked if he ever started counting them. “Start? Hell, I can’t stop.” We had just finished placing one body at the end of a long row. Corporal Thompson stood arms akimbo as he allowed himself a wide look around. “Last night I tried to sleep, and it was like counting sheep. They just kept coming, one at a time, all night.”