[Tuttle wound up back in a sick bed, but had a kindred spirit for a ward mate.]

I had to give in and admit it – I was sick. Whatever I had caught which put me on a hospital ship a couple weeks ago never quite went away. I had shied away from tough living since then, never feeling quite up to it, but finally the bug caught up with me again.

Field hospitals were very busy this time, and they wanted to send me far back, even off the island again. This time I begged to stay close to the front. They compromised by shuttling me eastward over to where the land based facilities weren’t so busy with broken fighting men.

It was a jarring ride, even though our engineers have improved roads in the center of the island appreciably. A splitting headache, dry cough, and rumbling gut can turn the smoothest road into rough seas. I woke up miserable this morning on what I’m sure a healthy man would consider a comfortable bed, in the 40th Infantry Division primary hospital.

My roommate was feeling much better than I was. He had been there two days before me and was well over the bug that had laid him down. Master Sergeant Harold Elliot whiled away much of the afternoon telling me stories from Dodge City, Kansas. I wondered how a patch of table-flat farm land could hold many good stories, but Sergeant Elliot was good teller of tales. I didn’t mind his monologue one bit.

…

Finally he asked, “Don’t you ever get sick of it? Tired of writing the same story every time?” He hit a nerve. It was exactly what I’d been brooding over for days.

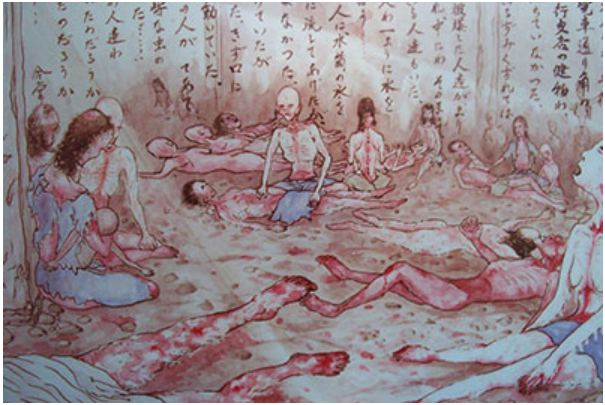

After every pitched battle I had to come up with a new way to say, ‘Things were destroyed. Men are dead.’ I had been at it for years. It seemed important, telling people what an awful spectacle I had seen. But somehow I still had to entertain them. I had to keep readers from becoming as numb as me and turning away from it all.

Sergeant Elliot perked up and leaned over closer at my account. “That’s exactly what I mean! I wanted to hear it from a civilian.” He confessed to me as a new found kindred spirit. “Honestly, there’s no solid reason for me to be laid up back here. I’ve been a lot sicker than this and stayed out on the line with my boys.”

He sat back against the metal headboard again and looked around the room, as if to make sure it was still just the two of us. “I’m just tired, sick and tired of it all.

Personally, I could get out there and fight forever, out on the line. In fact I was sure this was a job you just do until you get killed, no exceptions. But since they gave me those fifth and sixth stripes,” he pointed at his hanging service jacket, “all I do is feed good men into this… into that machine out there. It adds them up, spits some back out, and nobody knows how it decides.”

“And so what? So goddamned what?? These mountains, they don’t care. They’ll be here long after all of us. The ocean? It could swallow us all and not notice. Even the cities we think we destroyed, they’ll all come back. They won’t care one whit that their old people are dead, and if the new people are a slightly different color.”

The old master sergeant about had me convinced to resign, to give up and buy a struggling grape orchard somewhere. Since I didn’t have enough saved up to do that I continued the argument. We talked until well past the second lights out scolding from the floor nurse.

There was never a doubt that the sergeant would return to ‘his boys.’ He was part of the best chance they had to accomplish something, however indifferent the mountain might be to it, and to get back home alive. It mattered because they mattered.

We were people. Ultimately all we could worry about was people . The ambivalence of the birds we would have to live with, however many of us lived to hear them sing again back home.

I was suddenly impatient to leave my sick bed again. It felt like me getting out to witness things would help them along, just a little bit faster.

Yesterday a sand snake crawled by just outside my tent door, and for the first time in my life I looked upon a snake not with a creeping phobia but with a sudden and surprising feeling of compassion. Somehow I pitied him, because he was a snake instead of man. And I don’t know why I felt that way, for I pity for all men too, because they are men.

– Ernie Pyle, June, 1943