[Tuttle rode forward with a group of reporters to see the American line finally be joined continuously across Kyushu.]

1st Lieutenant Millard Wells drove his own jeep, which he succeeded in filling with three reporters. I rode in back with Bob Bellaire of Collier’s. John Elliot sat up front as the Australian representative.

It took some time to get back near corps HQ, continue southeast on a good secure (and freshly rebuilt) road, and finally get up to the front lines near Kagoshima Bay.

We turned the drive into an hour long press conference. Lieutenant Wells shared what he could about the larger situation. Fifth corps had top priority on everything for the current breakout – ammo, air support, even toilet paper stocks were advanced to keep the divisions ‘moving.’

…

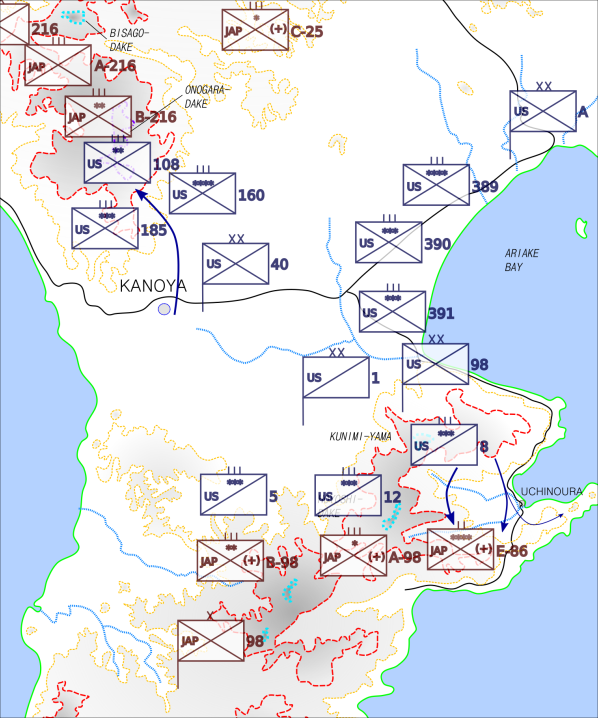

What Lieutenant Wells had gathered us to see was the planned meeting of American units at the north end of Kagoshima Bay. Once connected there, the American front would finally be one unbroken line all the way across Kyushu.

He described the shore there as dense with small cities. They were well situated as a hub for commerce, closer to inland parts of Kyushu than any of the larger ports. Industrial development of the coast was sparse, but in aggregate it was something worth taking.

Intelligence suggested the area was still well populated with people. The lieutenant didn’t know why, but it was another reason we had not and would not thoroughly bomb and shell the area before moving in.

We drove right to the water’s edge north of Kagoshima city. Lieutenant Wells pointed northeast across the bay. “That flat land runs north all the way into the next really big mountain [Karakuni-dake]. The 12th Cav already tried to get across once and got lit up by big artillery. Then them and the 158th [Regimental Combat Team] got shelled at random all night after pulling back.”

I asked the lieutenant if there was anything we were going to do about the long range artillery before they moved out again. He hesitated a moment then answered without looking away from the road ahead, “Not really. Heavy bombers will carpet the mountains, but they did that twice already.”

This morning found me situated with forward observers for the heavy mortars of the 322nd Infantry Regiment. We were staked out on a small hill, hurriedly cleared of brush, looking down into one of the coastal towns on the north end of Kagoshima Bay.

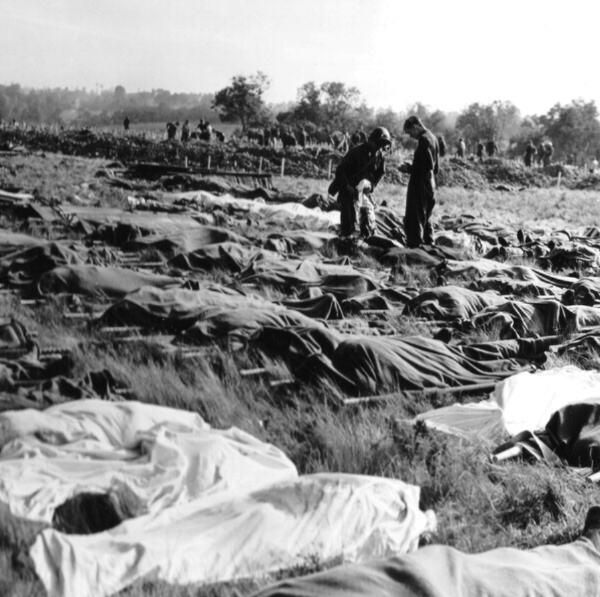

Behind us was a similar town, one held by American forces for many days. That town had experienced tough urban fighting, followed by heavy artillery fire from the recently pacified Sakura-jima. It was less than a ghost town. Its few charred remaining buildings offered no outline of the former city streets. Paths cleared by American engineers went straight through, with no thought to the original map.

The town ahead was pristine. One could imagine people getting up for work that morning, and children running off to school along the quiet safe streets. In fact, a keen eye could pick out heat and faint smoke from cooking fires down below. I didn’t think they had made enough breakfast for the ten thousand guests they were about to get.