[Not included in the original Kyushu Diary, this Tuttle column is often reprinted on Chirstmas Eve. We share it this week marking the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.]

I made reference back on the 7th to the Pearl Harbor attack of 1941. For me this date, December 24th, Christmas eve, will always remind me more of that horrible fateful day. Because the destruction from the attack didn’t end on the 7th. One story of loss will stick with me. On December 8th tapping was heard from deep inside the partially sunk battleship West Virginia, where some number of men were trapped deep below deck. On December 24, 1941, the tapping stopped.

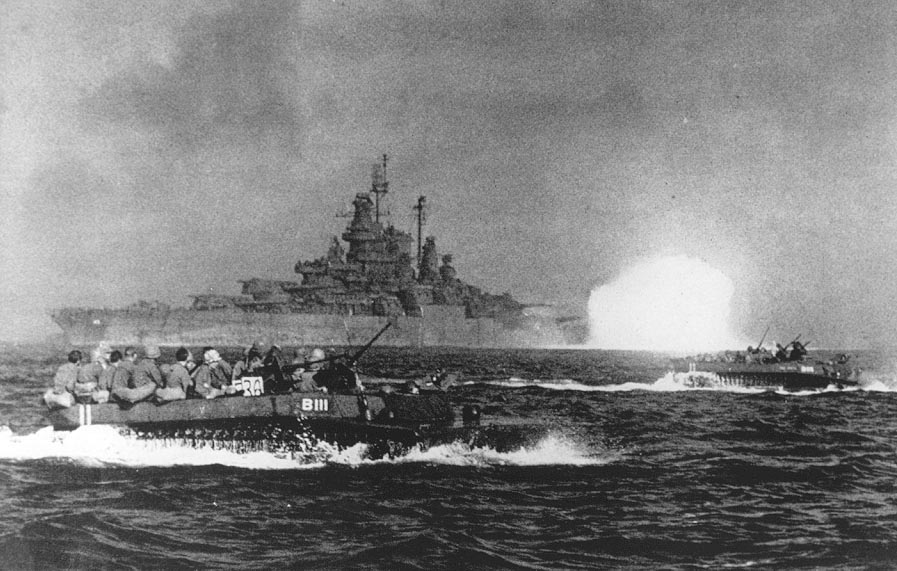

The West Virginia is here with us now, along with four of her sister ships from Pearl Harbor’s now infamous ‘Battleship Row.’ The trouble with sinking ships in a harbor, especially Pearl, is that you can’t. It’s too shallow. Big ships settle on the bottom, still half above the surface, and a good harbor has every facility one would want to patch up and re-float the ships. In fact the Nevada, the only big ship to get under way that morning, was deliberately grounded after she took damage so she could be recovered and repaired.

The hit at Pearl was a big one for sure, and permanent for thousands of young servicemen, but for most of the big ships ultimately only temporary. Certainly Japanese planners knew this going in. The U.S. Pacific Fleet was mighty thin for the next year, reduced to hit-and-run harassing strikes with the carriers that by luck weren’t there in Hawaii. But since then, with scores of new and repaired (and upgraded) big ships joining the fleet, it has leapfrogged the worst nightmares of those admirals in Tokyo.

Much has been said about fast aircraft carriers taking over from the battleships of old as kings of the sea. That may well be true on the ocean, where fleets have engaged in air duels well out of gun range many times across the Pacific. But here on dry land, I can certify that the battleship is very much respected, or feared, depending on which side you’re on.

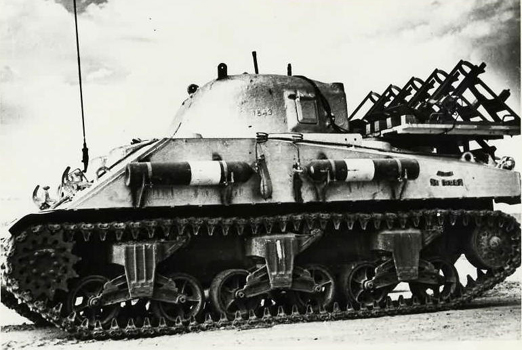

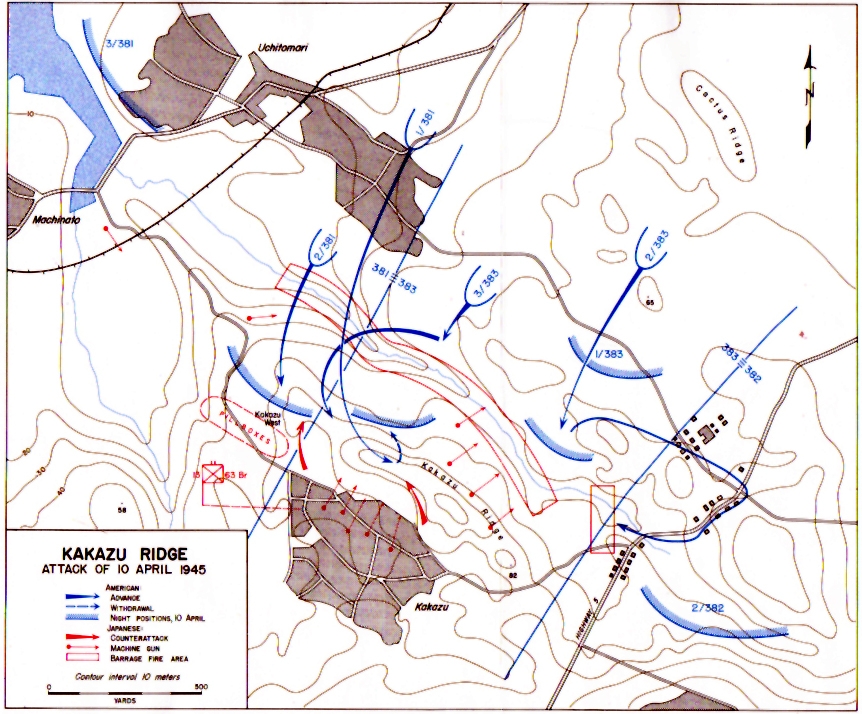

Navy ships sail with bigger guns than any army even attempts to drag along on land. Any place on the Earth within twenty miles of forty foot deep water can be blasted by one ton shells from our newest big ships. Japan is an island nation, and all of her conquests outside of China have been more smaller and smaller islands. All of them are vulnerable to the wrath of naval ordnance over almost all of their surface. Planes could drop bombs of the same size, but low flying planes can be shot down with the smallest of anti-aircraft guns. The only defense against navy guns available to most Japanese garrisons has been to dig and dig and dig, deep down into the rock if they can, and wait to be flushed out by flame throwers once the Army or Marines land under the support of those big old battlewagons.

Here on Kyushu, we found the main beach defenses lined up just exactly beyond the range of most navy guns. At Ariake there were the reverse-slope positions our Navy couldn’t get at until sailing into the bay, and that cost us something. But outside of that, the best tactic the Japanese had was to leave old guns in dummy installations near the shore to soak up shell fire.

The ships that came back from the knock-down at Pearl Harbor were mostly older slower vessels, but they work just fine for work along the shore. Islands don’t move very fast after all. The battleships have been kept very busy. The USS New York just rejoined the fleet after having her guns re-lined. They were worn out from firing so many thousands of big shells at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Back to the story of the West Virginia. Re-floating a damaged ship does take some time. She didn’t make it into dry-dock for repairs until June 18, 1942. Before that many attempts were made by divers and search teams to enter the lower compartments and rescue survivors or recover bodies. That is also necessarily slow work. Cutting into a closed compartment will flood it, and possibly many more compartments if the hatches aren’t all closed. Letting a lot of air out and water in can destabilize the whole ship, sending it over and ruining all chances of rescue or recovery.

I have it on good authority, but off the record, that three young men were recovered from the last compartment opened on the West Virginia. By match light they had marked off the days on a calendar through December 23rd. The Navy has decided never to identify them. They will be officially listed as Killed-In-Action, December 7, 1941.