[This is the preface from the book X-Day: Japan.]

Guide for the Modern Reader

The book Kyushu Diary was originally published in 1946, in which Walter F. Tuttle combined his own columns and other notes into an edited compilation. The second edition of 1952 was also by Tuttle’s own hand, with added footnotes, a map, some previously censored sections, and a post-script from the author. We are not calling this new book a 3rd edition. We have left Tuttle’s own 2nd edition of his compilation intact. X-Day: Japan starts with the second edition of Kyushu Diary and expands on it with extra features for a 21st century presentation.

The target audience of Walter F. Tuttle’s original Kyushu Diary is a newspaper reader of 1945. That person speaks a slightly different language from someone in the 21st century. That reader was persistently exposed to an argot of military affairs during six years of global war. Some of the words and concepts novel to that reader are mundane to us now, and many common phrases or jargon of that fast-changing time quickly became anachronistic or forgotten.

Tuttle wrote that “logistics” was a new word to many people then, as fielding a large army into undeveloped territory across a vast ocean was an unprecedented concept. In our modern post-jet-age economy, “logistics” is found in perky ad slogans of major companies.

Our modern world has been shaped by things we call “low intensity conflicts”, “limited war”, and “counter-terrorism operations”. These are all terms that would have been completely unknowable to a reader of the pre-nuclear 1940s. To help the modern reader bridge those gaps of time and language, we have included a section of brief historical context, and a small glossary.

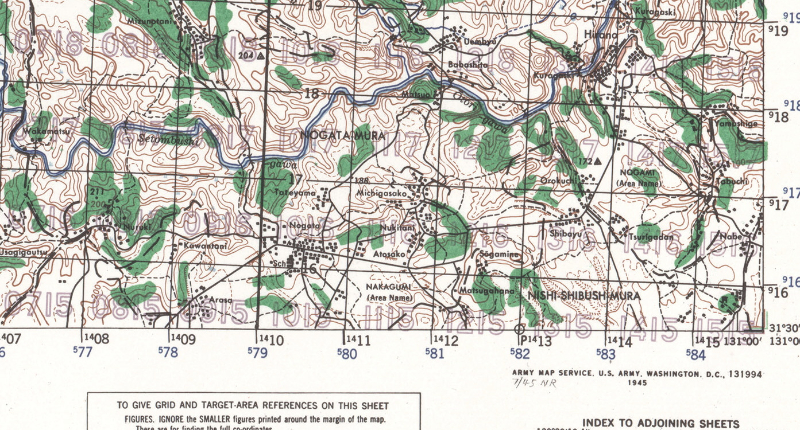

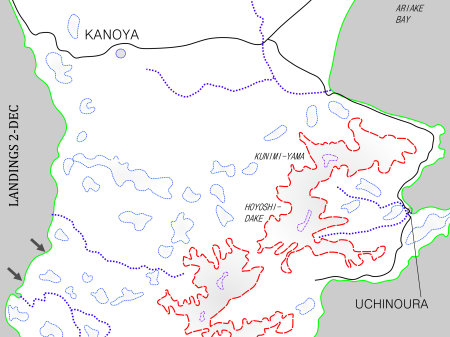

Histories are generally either top-down views, summarizing the whole situation, or narratives from an individual perspective. Tuttle’s Kyushu Diary is at its heart a personal narrative. But Tuttle went to some trouble to paint a complete picture of the scene in the Pacific, from the home front all the way across to the battlefields in Japan, for the benefit of American readers who had been shown mostly news from Europe in the preceding years. Toward that effort we add this guide, additional maps, a list of further reading, and a judicious few additions to the text footnotes.

Tuttle believed in the spontaneous uncertainly of momentous events, which could turn out vastly different from changes in decision making or from natural flukes, and he was keen to communicate this to readers. In that spirit we also include a list of books of alternate histories or historical fiction novels, fantastic explorations of entirely possible what-ifs in this part of history. Popular topics in this genre are ‘What if we forced Japanese surrender by dropping atomic bombs on cities instead of military targets?’ and ‘What if we dropped atomic bombs on cities and they kept on fighting anyway?’

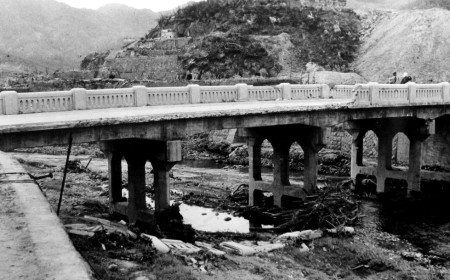

The book is not a parade of military hardware or a treatise on combined arms tactics. It does not get into any high level politics or command decisions. As before the war, Tuttle wrote about people and how they over came their own local problems. As a reporter he provided regular updates about the progress of each battle and the larger situation, but his real interest was in setting the stage for human stories to play out.

The text of Kyushu Diary varies considerably from the columns that were published under Tuttle’s byline during the war. The columns were worked over by many editors, and parsed out to fill some number of column-inches three days a week. Tuttle did not actually write to a format or deadline; he submitted when he could. The book was written directly from Tuttle’s own notes and original submissions. Many boring days are skipped, and some busy days have a dozen pages of dense material. That’s war for you.