With dusk approaching, 2nd Division HQ sent a jeep bound runner out to check the disposition of all its units before nightfall. I hitched a ride along to see for myself.

Our driver was Corporal Don Blue, who said he drove a county snow plow back in central Michigan. His slick-road experience paid off, since days of intermittent rain left the winding dirt roads we had to use persistently hazardous. This section of Kyushu is composed entirely of similar rolling hills, covered in modest evergreen trees or cleared for small terrace houses and farms.

Back near the beach everything had been completely leveled – buildings, trees, and anthills. It was perfect desolation, oddly beautiful as the smoke cleared revealing its special sort of purity. Further inland some of the hill faces are partly denuded, from shell impact and fires kicked off by incendiary bombs, but the spread of fires had been damped by regular rains. A constant smell wafts through the winding valleys, mixing churned earth with burning pines, gunpowder, and occasionally cooking meat.

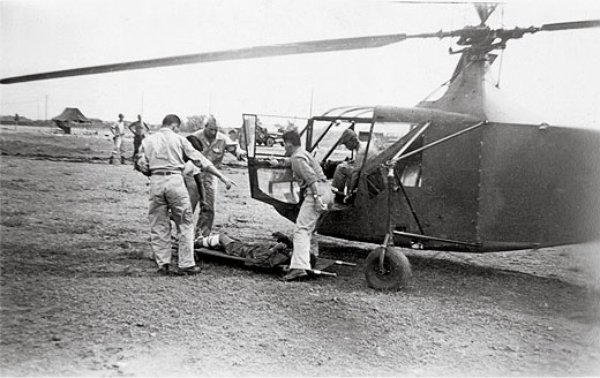

Going forward most of the narrow road way is bracketed by a three or four foot high stone wall to one side and a similar drop-off to the other. Traffic knots are inevitable, even for ambulances trying to haul men back to the beach front.

Navigating through it all in the other front seat was 1st Lieutenant Martin Myers. By map, temporary signposts, and a few hollered exchanges with knowledgeable looking men on the ground, we reached each regimental headquarters. Lieutenant Myers conferred with the XO of each unit to get a face-to-face run down of how they were doing and what they needed. He would take back any priority written items for HQ or division intelligence.

I wandered around outside at each stop, taking in the action. Everything up here, just a mile or two from the very hot front line, is transient. It could fall under attack at any time and will probably move again in a day or two. Yet still there is an insistent order to each outpost. Engineers were busy making a clearing to expand a tent-bound medical aid station. A kitchen unit marked out space to work, with a dedicated lane for trucks to pull in, load up, and haul hot meals as far forward as they could be served.

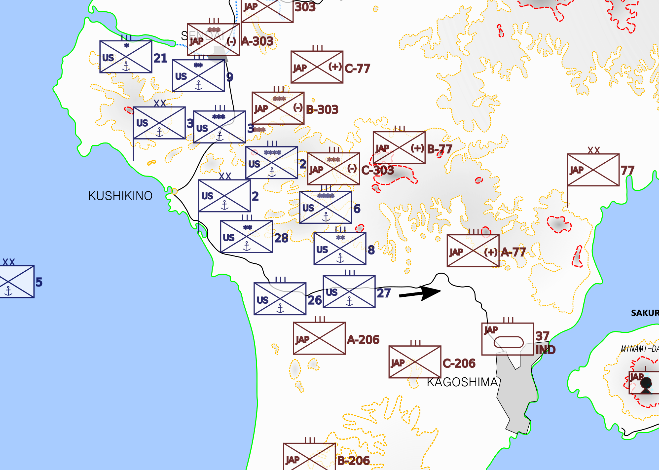

With limited light to drive by, we hustled back while Lieutenant Myers caught me up on the rough details of his scouting mission. “We’re about four miles inland, all along a fifteen mile front. Third division is holding at the edge of Sendai and cleaning up the chunk of land left of them out to the sea.” He pointed on a map to the lumpy peninsula that was defined by our beach head and the wide Sendai river. “Second division here is holding the same way, already stretched out thin and waiting for the Fifth to land before making another move.”

I asked how well off the units were, as we pulled over to let a line of ambulances get by. “Truth is,” the Kansas City, Missouri native admitted, “they’re pretty banged up. Everyone’s reserves are already committed. We plan a morning rush to lock up the first good line of hills.”

He pointed again at the map, touching contour bubbles in a line southeast from Sendai. “That bunch of hills will be a great place to be once we take it. Thing is, that works both ways. The Japs here are dug in on all sides and not budging. Every move we make to dig them out is spotted and opposed. These guys so far seem lightly armed, but they call in some heavy stuff from the hills behind them.”

Glancing back out to sea the Lieutenant added, “The Navy has been hot and fast with fire support, but the Japs hide on the reverse slopes most of the time and there are so damned many trees we can’t spot them until too close most of the time.” He made a sweeping gesture at the forested hillside next to us. “Even if we had enough rounds to level all the trees, it would make an impassable pile of logs, a sniper behind every one.”

Once the immediate objectives are taken, the Marines will have fought uphill about 1300 feet from the sea. I noted that beyond the first prize ridge line sits another. After that the hills become mountains that have names. Here on Kyushu there is always one more hill beyond the one you just conquered, and it’s always just a little higher.